Time, as this Digiday story points out, has been aggregating articles from some of its corporate brethren under its own banner. The goal, as the story says, is to provide a broader range of content than what Time would normally cover and hopefully not just raise awareness of those other titles but also build loyalty for its own brand, all while using cheap content.

Time, as this Digiday story points out, has been aggregating articles from some of its corporate brethren under its own banner. The goal, as the story says, is to provide a broader range of content than what Time would normally cover and hopefully not just raise awareness of those other titles but also build loyalty for its own brand, all while using cheap content.

But the question has to be asked: Does anyone care about the Time brand? More broadly, do fewer and fewer people care about media brands as a whole? Consider the following:

What network broadcasts Modern Family? Hulu. When do you watch Parks & Recreation? Whenever there’s time because it’s saved on TiVo. What’s your number one news source? Feedly. How do you find out about breaking news? Twitter. Where do you turn to for more information? Google. What label is Radiohead signed to? Spotify.

Yes, some of that is a bit generalized and it certainly betrays the thinking of someone who’s a power user in many regards, but I’m willing to speculate that there’s more than a bit of overall truth in there. Consider three recent stories:

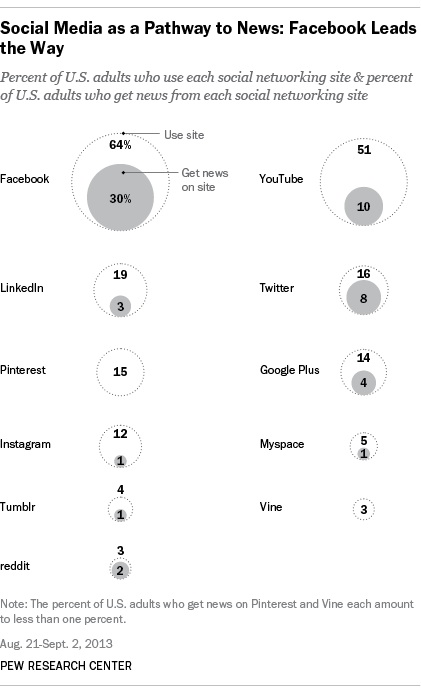

First, the Pew study (which I’ve mentioned before) that goes into how people are relying on Facebook, YouTube and Twitter (in that order) for news, though you can argue about the definition of “news” when discussing the results of that story. Despite that, this is the channel where people are expecting to have the news come to them as opposed to them having to go find the news.

Second, a recent study that showed across all categories that organic search drove 51% of site traffic, something that has to be seen in the context of a number of studies and surveys that show search-generated visitors have much lower loyalty rates and time-on-site averages than those who visit the site directly, using through either a browser bookmark or just typing the URL into their browser.

Third, the news that TV networks will be projecting for anticipated seven-day viewing when they release their overnight ratings numbers, an admittance that the number of people watching TV in “real time” is getting smaller and smaller, to the point where ad revenue could theoretically not support the broadcast model if it were based solely on that overnight number.

Put that all together and you can see a shift away from the First Publisher model in favor of one that is more loyal to the delivery aggregation model. People want their TV to come in this way, regardless of when it’s broadcast or what network it originates on. People want their news in a manner of their choosing and not based on old media print models, something that’s covered by PBS Mediashift as they discuss how advertising requirements are holding back innovation in magazines on tablet devices.

It’s not, I don’t think, that people are wanting vastly different kinds of content, be it news stories or video or anything else. It’s that they are far less picky about who it is that can provide them with the kind of content they want. That means less brand loyalty for those First Publishers and more loyalty to the aggregators, the funnels through which the content comes from the sources and into their lives.

This is a reality that everyone needs to start adapting to. In a lot of ways it makes more sense for the publisher of Time, Sports Illustrated and other magazine brands to not just offer these individual imprints but also offer an app that is inclusive of all their content and which breaks down content based on type and which allows for people to build their own experience. That’s exactly how the updated Circa app as well as the Inside news digest app work and it makes a lot of sense. I want a mix of politics, entertainment news and a few other things, all in a single app. They’ve allowed me to get the news I want when I want it, a setup that, as that Mediashift story points out, the traditional publishers are unable to adopt because their advertising model actively discourages it.

So here are some media consumption realities that need to be kept in mind:

People have shown a willingness to pay, either directly or through attention (meaning exposure to ads) for all-you can eat subscriptions. Netflix, Hulu Plus, Spotify, Pandora and others show this clearly.

People have shown a willingness to pay for or at least actively choose aggregators that cut out the content originator. See TiVo, Circa and other funnel-type tools that show this.

People have shown a willingness to pay directly for content that cuts out the broadcast model completely. See Apple TV, Amazon Instant Video and other on-demand services for evidence of this.

All that adds up to one thing: The need for drastically different models to be put into place. And if the last few years are any indication if the content originators won’t do this then someone will innovate on their behalf and cut them completely out of the equation based on consumer desires.

Like this:

Like Loading...