Simon Cowell sent the news of “The X Factor’s” renewal for a third season out to his nearly 4.5 million Twitter followers long before Fox issued an official press release. Stephen Amell, star of CW’s “Arrow,” tweeted the news of the Warner Bros. TV frosh drama’s back-nine order nearly an hour before CW issued a statement from network topper Mark Pedowitz. “Best way to start a Monday?” Amell wrote. “Getting picked up for your back nine episodes. Thwick.” Not to be left out, “Raising Hope” star Lucas Neff let loose with the news that his Fox laffer had been given an order for an additional two episodes this season.

*Disclosure: Arrow is related to some client work that I do, though I’m not involved in that portion on a daily basis.

The Variety story is focused on how it’s a scary new world for PR pros, who are often taken off guard when talent decides to go it alone and break big news on their own. But there’s more to the story of how the press has fed that behavior, what it means for the traditional definition of reporting and what value then the media gatekeepers have for an audience that can get the news straight from the horse’s mouth hours before a story is filed.

Believe it or not I’m not going to come out and say the idea of “the press” is passe in a world where stars, athletes and corporate executives can say whatever they want to say (on Twitter, a blog or anywhere else) whenever they want to. Quite the contrary, in fact: The press plays an even more vital role in that world since they’re the ones who can go beyond the “yay, us!” sentiment and spin and get to the real story. The press serves an essential role of checking the statements made by those parties against reality.

In other words, the job of the press has not changed.

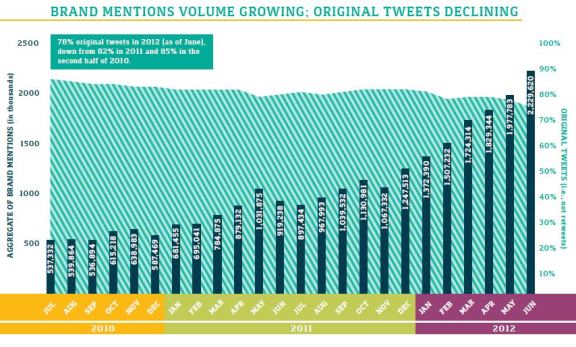

What has changed for them is the idea that they have some sort of exclusive access to newsmakers of any stripe. When the public can get the news, gossip and opinions of people they find interesting directly then the role of the gatekeeper is very different. It’s not just that news outlets simply need to be monitoring Twitter feeds to see what people are saying so that they can throw the text into a graphic and display it over the left shoulder of a morning show anchorperson. Doing so shows that the news organization has nothing to add and positions them as being essentially irrelevant. They also need to add context behind the quote. Why did they say that thing, at that time, to those people in that venue? What’s the story behind those <140 characters? If that’s missing then, yes, there’s no reason for me to watch your news program or read your newspaper.

For PR professionals who are seeing these people go off the reservation and lay to waste their carefully assembled plans, the role *has* changed more substantively. In one scenario they can rail against it and tell everyone to STFU until after an embargoed press story has broken. In another they can co-opt this change, bringing a celebrity and their loyal Twitter followers into the plan and making it an essential component in a very formal and, let’s face it, stilted way. In a third scenario they can leave the celebrities, CEOs and others to do what they’re going to do and come up with a plan that doesn’t factor their behavior in at all.

Each scenario has its benefits and may be rightly applied in different situations. But unlike the press, the job of the PR professional has fundamentally changed. A stray tweet can mean life or death for a plan that’s been in the works for months and therefore needs to be accounted for in some manner.

This is an odd world we find ourselves in, where so much news is broken on platforms and channels that aren’t owned by some sort of organization. The appropriate response to the challenges and changes inherent in that new world isn’t fear, though. It’s adjustment.

Jack Dorsey of Square and Twitter wants us to get out of the habit of calling people “users.”

Jack Dorsey of Square and Twitter wants us to get out of the habit of calling people “users.”