There was a running point of disagreement I argued over and over again with friends involving Tom Petty, who passed away at least twice yesterday, if not more, his defiant spirit seemingly unwilling to slip this mortal coil. They would insist I had been among the group who had gone to see Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers at Poplar Creek during what would have been their tour supporting Into the Great Wide Open.

I never saw that show, a point no one in my group would concede. It would have made sense if I had, though. There were three or four of us – Todd, Craig and Howie – who would often go to concerts as a group, with others from our extended circles of friends joining as the situation would warrant. That’s what we did in the summers of our later high school and early college years, we went to concerts. And of course we were all Tom Petty fans.

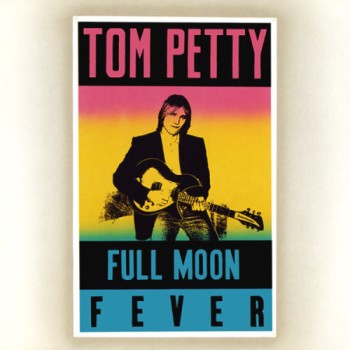

My entry point into the music Petty created was 1989’s Full Moon Fever. While I was certainly aware of and a fan of his music before that, diving into the Heartbreakers catalog was a bit intimidating. There were so many good songs that were in constant rotation on rock radio in the Chicago suburbs in the mid-80s as I was developing my own musical tastes I didn’t know where to start.

My entry point into the music Petty created was 1989’s Full Moon Fever. While I was certainly aware of and a fan of his music before that, diving into the Heartbreakers catalog was a bit intimidating. There were so many good songs that were in constant rotation on rock radio in the Chicago suburbs in the mid-80s as I was developing my own musical tastes I didn’t know where to start.

So Full Moon Fever presented an easy entry point. Like a long-running comic series offering a new first issue free from decades of backstory constraints, Petty’s first solo record presented an easy jumping on point. I could start here, I thought, and get in on the ground floor.

Actually…my first Tom Petty purchase was the cassette single for “I Won’t Back Down,” which featured “The Apartment Song” as its B-side. I bought that because I dug the song not only as a result of its radio airplay but it’s fun music video, a staple of MTV and VH1 at the time. The groove and chorus were masterworks in the essential elements of rock and roll. The video featured not only half of The Beatles but two-thirds of The Traveling Wilburys, whose first album was one I’d already been enjoying.

(Side note: I’d give anything to hear Ringo Starr’s drums on “I Won’t Back Down.” Like…what did that sound like as he was playing while shooting the video? Was it filled with that Ringo swing? These are the questions that keep me up at night.)

I listened to Full Moon Fever repeatedly, appreciating the simplicity of “Free Fallin’,” the driving beat of “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” the tight harmonies of the Byrds’ cover “Feel a Whole Lot Better,” the fatherly sincerity of “Alright For Now” and more. I chuckled in disbelief at the “Hello, CD listeners” hidden trick at the midpoint of the CD that marked the point where a tape or LP would have be turned over.

Full Moon Fever was just the entry point. I would buy plenty more albums of Petty’s, both his solo stuff and subsequent albums with The Heartbreakers. Those I didn’t buy I taped off the CDs of friends who did. Like everyone else, I bought the 1993 Greatest Hits album that collected the best of his catalog up to that point. I will argue with anyone who doesn’t believe the She’s The One soundtrack isn’t an absolutely essential Heartbreakers record. I don’t understand why a movie hasn’t been made based on the song “The Last DJ.”

Petty is one of the few contemporary songwriters who emphasized storytelling in his lyrics, part of why they connected with me – and countless other people – over the years in ways others don’t. Everyone writes pop songs about feelings and emotions or characters. But Petty knew how to tell create an arc, every song a three to five minute John Barth-esque short story that took you through the entire journey of an individual.

The protagonist of “Runnin’ Down A Dream” is on the hunt for something vital to his life. The radio personality of “The Last DJ” is mounting a one-man defense against homogeneity. Johnny’s entire career is summed up in “Into the Great Wide Open” and, if you’re anything like me, revisited in “Money Becomes King.”

That puts him in a rarified company that includes Bruce Springsteen, Steely Dan and few others. He’ll share a story that is relatable to everyone, understandable by a few and which comes out only upon repeated listenings because you’re too busy the first time soaring with the guitar solo or tapping your foot along with the four-on-the-floor drum part. Only then do you discover the insightfulness of the message he’s proclaiming, following along with the story of a girl realizing her identity in a California town or a man declaring his unwillingness to fall in the face of adversity.

Petty’s inclusion in The Traveling Wilbury’s always seemed apt to me. While he wasn’t much younger than anyone else in the group – 14 years younger than Roy Orbison but only three shy of Jeff Lynne – he seemed to be a bridge between musical generations. Influenced by The Beatles and The Byrds, The Heartbreakers’ first album came out just seven years after Let It Be. All the members would put out albums in the years around the time of The Wilburys’ Vol. 1 but Petty still seemed so vital, so current, that it seemed as if he were of a whole new era.

When artists like Petty pass we reflect back on the work they’ve left with us and mourn the reality that no more will be added to that body. It was thus with Prince, David Bowie, Glenn Frey, Chuck Berry and everyone else we’ve lost not just in the last couple years but throughout time. We think, as I’ve done, about the moments we first connected with that artist and what he or she meant to us.

In my listening, Petty has always provided an essential element of sly simplicity. It’s likely the lasting influence of the “I Won’t Back Down” video, but I’ve always listened to much of his music imaging a slight smirk on his face, the kind of expression worn by someone privy to a joke not everyone can see. Perhaps it’s just that he’s doing something he truly loves and making a good living doing it, a claim not everyone can make. It’s a smile that shows up in the live performances I’ve watched online, including his famous Rock & Roll Hall of Fame collaboration with Prince and others on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” in tribute to his friend and collaborator George Harrison.

Tom Petty always seemed unpretentious in the interviews I read, reluctant to talk about his music because that’s what the music was supposed to do, aware of the legacy he’d already created and would eventually leave behind but not slavish to it or lackadaisical because of it. In the end he left with a catalog that contains few, if any, notable weak spots. Like him, it’s unpretentious, with tunes that will stay in your head for days and lyrics that only expose their true meanings over time.

I never saw Tom Petty perform live myself, despite the insistence of my friends. That’s alright, though. His music was always there, hanging around the sidelines of my life, and that was always enough.

Chris Thilk is a freelance writer and content strategist who lives in the Chicago suburbs.